Spider-Man is the most famous Marvel character, bar none. Even people who’ve never paid a damn bit of attention to comics know Spidey. Look, the guy’s been the subject of SIX big-budget Hollywood films (which means he’s at least tied with Batman and Superman), and at least half-a-dozen animated series, as well as a short-lived un-animated series in the late 70’s (even if was lousy) (PS – there was also a live-action Spidey series in Japan). Plus toys, books, a newspaper comic strip and god knows what else. Spidey is as close to a household word as superheroes get.

Actually, I first met Spidey not in the comics but in the Grantray-Lawrence animated series from `67, which was in re-runs c. `71 when I first saw it. The GL series was a cheap, crude and odd beast – the first season was a simplified but pretty straightforward adaptation of the comics – most of the stories were based on issues, or if not, at least used Spidey’s established pack of villains and supporting characters. The second season, which was helmed by Ralph Bakshi, turned into a bizarre psychedelic sci-fi fest that had little to do with the comics but was fun to watch.

In any case, Spidey was commissioned by Stan Lee but devised by Steve Ditko, one of the oddest artistes ever to grace a comics page, both in artistic style – Ditko drew odd, skinny, balletic-looking characters and the weirdest aliens and monsters imaginable – and in person – Ditko was a reclusive, anti-social, Ayn Rand-devoted oddball. He died this year in near-total poverty.

Ditko had a bizarre and wild imagination. His forte, pre-Spidey, had been short

fantasy/sci-fi tales with weird twist endings, and really weird

characters. Even his most normal

depictions had a strange, unearthly quality.

And when he let his imagination off its leash, as he did especially with

his other major Marvel creation, Doctor Strange, the results were positively

lysergic.

The most remarkable thing about reading through Ditko’s run

on Spidey – basically the first three years – thirty-eight issues plus two

annuals – is that while Ditko certainly put a unique and distinctive stamp on

his run, he also established so much of what Spidey would continue to be to

this day in that short, long-ago period of time.

It’s also important to note that, as with Kirby on his

titles, Ditko is the one to credit.

While the initial development may have been collaborative, the stories,

themes, and characters in the Ditko Spider-Mans are consistent with those he

would develop in subsequent projects over the years. One need only look at the post-Ditko

Spider-Man issues to see that there’s simply no way Stan had the imagination or

the inclination to have mined that territory.

Reading these issues again today, these are the things that leap out at me from Spidey's original run...

The Superhero As Prize Dork

Superheroes were generally millionaire playboys who no one thought would put their asses out there in danger. The exceptions still didn’t stray far from a certain alpha-male-ness. Billy Batson might’ve been a kid, but he was a cool kid. Don’t say Clark Kent – sorry. Even if he wore glasses, Clark was obviously manly as hell.

Peter Parker, on the other hand, was a dork. Skinny. Bespectacled. He wore sweater vests and bow-ties for fuck’s sake! Jocks picked on him and girls ignored or laughed at him.

He was forever at the mercy of Aunt May, a mummified sweet-natured crone who mother henned the kid ad nauseum, always exerting him to wear his galoshes, watch out for wind, rain, roughneck kids, anything else she was afraid of – which seemed to be everything under the sun. Aunt May thought Spider-Man a terrifying criminal, and expected Pete to stay away from anything that might risk a bruise. She didn’t like slang and she expected him to dress properly, so all around Aunt May cramped Pete’s style as a high school kid and was an obstacle to work around in his superheroing (though she obviously must not have been very attentive, given how much the guy snuck out at night).

The whole Aunt May thing was mostly played for laughs, but Peter’s devotion to her was no joke, and several stories, plus his entire motivation for becoming a photographer, came from his attempts to support and protect her.

The Superhero As Angst-Ridden Teenager

Johnny Storm aka The Human Torch had already set Marvel’s standard for a more realistic teenage hero, but the Torch couldn’t have been more opposite to Peter Parker. Johnny Storm was a jock, a loudmouth, and, let’s face it, was never depicted as any kind of intellectual.

Marvel may also have already given us the self-loathing, morose Ben Grimm, but Peter Parker was a much more relatable angst-ridden teen. It’s said that Ditko researched teenage psychology as material for his stories, and that may be true. Peter/Spidey was moody as hell, confused, prone to fits of despair and frustration. As early as ish 3 Peter was throwing out his suit and quitting for good (something he would do many more times), after having his ass handed to him by Dr. Octopus (an inspirational talk from The Human Torch changed his mind). In point of fact, Peter is a right ass in his debut story, a self-centered, angry jerk blowing off everyone around him, until he learns his painful lesson about great power and responsibility.

He also did share one trait with Johnny Storm – a fearsome temper. Out of costume, he would periodically start to blow and have to pull himself back. In costume, he didn’t always bother. It didn’t happen often, but from time-to-time Spidey would simply lose his shit and leave even the hardest villains running in terror. The rarity of such moments made them all the more startling.

And, while other superheroes’ secret IDs were little more than color or occasional plot points, Peter’s soap opera soon took over the comic, the foibles and frustrations of his civilian life taking up as much as a third of any given issue, and becoming increasingly intertwined with his life as a super-hero.

The Super-Hero As Social Outcast

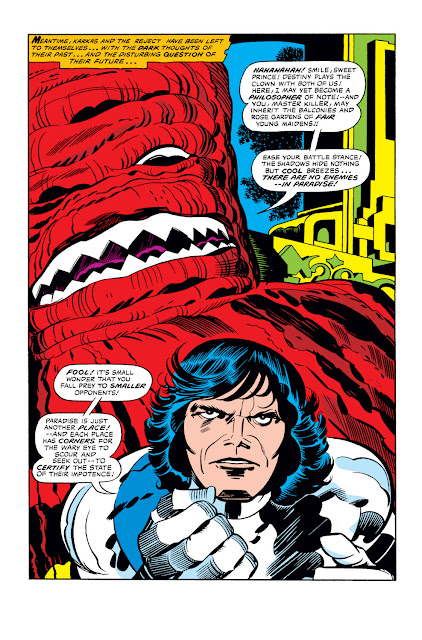

A continued theme in Ditko’s work. Post-Spidey, Ditko’s creations consistently operated outside of society and were often vilified for it. The Creeper was condemned by the media and hounded by the cops. Shade the Changing Man was a fugitive from justice. Mr. A and The Question were crazed, loner vigilantes. Even the more innocuous Blue Beetle was distrusted, while the super-powered Captain Atom was considered a dangerous menace.

Peter Parker was social outcast for being a dork. Spidey was a social outcast for being a vigilante, and hey – he was spider-y! Ick!

Ditko jumped on this theme out the gate of ASM #1, when news publisher J. Jonah Jameson begins regularly editorializing against Spidey, even after the web-head rescues Jameson’s astronaut son from a space capsule crash (caused by Official First Spidey Villain, the otherwise forgettable Chameleon). Jameson simply concludes that Spidey himself sabotaged the capsule in order to make himself a hero, anticipating Donald Trump by more than fifty years.

Jameson immediately became a significant supporting character, continually railing against Spider-Man no matter how many good deeds he did (including saving Jameson’s own ass on numerous occasions). Mostly played for laughs, Jameson carried on as a lunatic crank, who eventually extended his hate to all super-heroes – but always with Spidey as Numero Uno. He continues to be a pest to this day.

The Super-Hero As Sad Sack

As if all this weren’t enough, Spidey had the worst record for stupid things happening to him imaginable. Losing his costume and not being able to sew a replacement fast enough. Underestimating villains and getting his ass waxed. Even being mocked by little kids. Not to mention sometimes just plain fucking up. Parker’s luck was mostly all bad.

The Superhero As Wise-Ass

Superheroes had always been prone to making quips while punching out crooks, especially Batman and Robin. Spidey, however, was the first superhero to weaponize sarcasm and a smart mouth. Whether to cover for his own fear, to goad and piss off megalomaniacal opponents (all super-villains are megalomaniacs, but Spidey’s enemies seemed to be especially so, even by expected standards), or just cuz, Spidey always kept up a steady stream of smart-assery all through his battles. There was also the additional fact that his mouthing off was usually pretty damn funny.

Villains

Only Batman could boast a rogue’s gallery as impressive as

Spidey’s, and all of them were

introduced during Ditko’s run. Ditko

throughout his career introduced odd, quirky villains. Even the least of them had a memorable

quality. Conversely, post-Ditko, the

only major villain introduced for decades was The Kingpin, an overweight mob

leader. Only Ditko could have conceived

of the freakshow of baddies Spidey came up against.

Spidey’s first big foe was The Vulture, a craggy old guy

with mechanical wings. Not so impressive

at face value, but Ditko gave him speed, maneuverability and smarts that made

him pretty formidable. Interestingly,

The Vulture was pretty much pure criminal, primarily interested in stealing and

occasionally taking revenge on people who pissed him off (namely Spidey).

The Sandman was a brutal thug who could turn his body into

various consistencies of sand. For a

dumb guy, he could be pretty inventive with his powers, and gave Spidey a run

for his money (he later became a major menace to the FF) when he showed up,

though he often came to ignominious defeats (sucked into a vacuum cleaner, et

al). Unlike in the films, Sandman was a

pure brute with no redeeming qualities. The

Lizard was Curt Connors, a scientist experimenting with formulas to cause new

limb growth, whose experiments transformed him into a lizard-humanoid bent on

leading the reptiles of the world against the human race. The Lizard was savage and homicidal. Spidey managed to find a cure and made

himself a permanent ally in Dr. Connors and his family. Connor would re-appear later in Ditko’s run,

though not as The Lizard. Electro was an

electrified electrician (say that three times fast) who could throw lightning

bolts and give off massive electrical charges.

Like The Vulture, he was mostly in it for the money. Mysterio has to be the classic, ultimate

Ditko super-villain – a guy

wrapped in a flowing green cloak, with an opaque

inverted fishbowl for a head, surrounded in a cloud of fog. Mysterio seemed to have unlimited

supernatural powers, particularly his habit of raising that cloud of fog and

disappearing. It turned out all his

powers were clever tricks, but Mysterio was a rare super-villain whose gambits

involved fucking with Peter’s mind far more than fighting him. Added to Mysterio’s own innate bizarreness

was the surreal nature of his escapades.

He was rarely used, even after Ditko left, but the decidedly weird

storylines that accompanied him during and after Ditko were always

memorable. Curiously, there’s a bunch of

online polls showing him as one of Spidey’s least respected villains, but every

Spidy-phile I know loves Mysterio. Kraven

the Hunter was a wildly-constumed super big-game hunter whose goal was to hunt

Spidey down like an animal, in the urban jungle. He made a couple appearances, but one was

little more than a re-take of the first.

It took Mike Zeck and J.M. DeMatteis to figure out what do with

Kraven. The Scorpion was one of several

baddies (Kraven was another, and Mysterio too, for that matter) whom Jameson

paid to stomp Spidey. In this case,

however, he also paid for the guy’s costume and powers (a green suit and

transformation allowed him to climb walls, have super-strength possibly a match

for Spidey’s, and a tail that he could club things with).

Oh, and the Green Goblin.

Well, despite his rep over the years, Gobby wasn’t all that much of a

big deal in the Ditko era. Except that

he was always treated as a big

deal. He bowed in ish 14, tricking

Spidey into a battle with The Enforcers, a crime trio who’d previously tangled

with the web-slinger a few issues prior.

He was odd, of course (all Ditko villains were), with his Halloween-ish

appearance and weapons. But its clear

from this first story that Stan/Steve had big plans for the Gob – he gets away

clean at the end, leaving his intentions and his identity a mystery. This trend continued in his second

appearance, and his third. And

fourth. And fifth. Norman Osborn didn’t get formally introduced

until issue 37, but even then he’s clearly being set up for something

important, paying off crooks to off Spidey, and he’s revealed to be quite

corrupt, and hiding a sinister secret.

It might be noted that for years, Stan claimed Ditko left Marvel because

of the decision to have Gobby turn out to be Norm. I call bullshit, since Ditko was known to be

plotting those late issues, and clearly Norm’s mystery was building. (Actually,

Ditko left over money issues – Spidey had become a big moneymaker and he wanted

a piece of the action).

Most importantly, there was Otto Octavius, aka Dr. Octopus,

aka Doc Ock. Ock bowed in in

issue 3 and

remains a menace to this day. Ock was a

creep nuclear scientist who ended up with 4 robotic arms fused to his torso

after an atomic accident. It also made

him a bit crazy (though there were suggestions he wasn’t exactly Joe Normal to

begin with). Ock was continually

committing showy crimes in order to get his hands/etc on scientific equipment

and money, all to the purpose of some kind of experiment or research that was

never defined or explained – quite possibly Ock didn’t know himself. After his initial appearance, he also hung

out with shady underworld types. Those

extra arms were fearsome weapons and he wasn’t exactly easy to beat. Almost all of his appearances under Ditko

were in major storyline or plot points, and he was and is Spidey’s arch-foe, no

matter how often Stan argues for The Goblin.

All of the above builds to the “Master Planner” storyline in

issues 30-32, which features Aunt May falling ill due to radioactive elements

in her blood (a side-effect of a blood transfusion she got from Peter early on)

(why she didn’t become Old Spider Lady I can’t say)(given how many other

supporting characters have become Spider-powered over the years, maybe I

shouldn’t go giving Marvel any ideas). A

criminal called The Master Planner is sending out teams to steal scientific

equipment – Spidey has several inconclusive run-ins with them. When they steal a serum that can save Aunt

May, Spidey loses it and runs all over NYC, terrorizing criminals for

information. All of this leads him to

the lair of the Master Planner, who turns out to be Doc Ock. After a brief battle, Ock, realizing that

Spidey’s out of control, pulls the ceiling down and escapes, leaving Spidey

trapped under tons of steel. Spidey,

trapped and helpless, works himself up from defeat and despair to

determination, and throws off the debris in a spectacular panel that ranks with

Ditko’s best work anywhere. It was a

hell of a story.

After issue 15, Ditko, like Kirby during his final phase,

seems to have been holding back on new characters. Most issues were filled with either retuning

villains, or second-rate new ones. This

is not the same as saying these later stories were bad (some of them were among

the best the series would offer).

Supporting Cast

Over time, Peter Parker's personal life, and the people in it, became every bit, if not more, important than the superheroics.

Flash Thompson was a knuckle-dragging jock who taunted Pete endlessly for daring to do things like read books and be interested in science. For amusement’s sake, he was also Spidey’s biggest fan and continually defended his hero’s rep whenever anyone suggested that Jameson might be right about him. After Pete finally breaks down and fights him in issue 8, knocking him cold, Flash starts occasionally showing a microbial fraction of respect for his rival – and avoids ever fighting him again, despite boasting that he’d destroy him if he did.

Harry Osborn got introduced in issue 31, as a loud-mouthed little pipsqueak with bad hair and a penchant for bow-ties. He quickly became Flash Thompson’s wingman and spent his time taunting Peter and trying to impress Gwen Stacy, the University’s icy beauty. Harry later inexplicably became Peter’s best friend, though it was hard to see why Peter, friendless though he mostly was, would want to hang out with Harry even after he started acting semi-human.

Frederick Foswell was a wimpy Don Knotts-looking reporter who set himself up as a crime-lord, but was taken down in issue 10. He reappeared much later with a more dignified appearance, working undercover in disguise as a crime reporter. Not exactly an ally of Spidey but sometimes useful, Foswell was a significant presence during Ditko’s final year on the title.

Luv Interest

Superman might have had Lois Lane, and the female hanger-on was a steady of superhero titles. It took the complex Reed-Sue relationship, the relatively realistic but light-hearted Barry-Iris in The Flash, and finally, Spidey, to bring some realism to romance in superhero comics.

Liz Allan started off as the unobtainable gf of Flash Thompson. But starting with ish 4, she accepts a sympathy date (which ends up not happening anyway) with poor Peter. None of this goes anywhere, but in ish 12, after becoming impressed with Peter’s courage in standing up to Doc Ock to protect Betty, she dumps Flash and starts making a play for Parker. Liz never did appear to be anything but air-headed and shallow, but all this did point to a major series development that I’ll get to shortly.

Peter’s chick-luck turns at the end of issue 5, when Jameson’s secretary, Betty Brant, starts openly flirting with him. By the end of issue 7, Pete is aggressively coming on to her (pretty damn smoothly, for a teenage dork, too!) Despite the sweetness of their relationship, Betty became a problem right quick. As early as issue 9, she was expressing her desire to not become involved with a thrill-seeking, danger-courting guy. Maybe not the best choice for a superhero. All this only got more complicated when Betty comes to blame Spider-Man for the accidental death of her brother in a gunfight in issue 11. Soon, Betty began displaying decidedly unlikeable traits, such as possessiveness and insane jealousy, mainly directed towards Liz Allan but soon to nearly every female short of Aunt May who comes within 10 feet of Pete. This trend soon went over the top, with absurd drama-queenish moments any time he wasn’t giving her his undivided attention. She began dating Ned Leeds, a young reporter for Jameson’s paper, and rubbing Peter’s nose in it (while still ostensibly being his girlfriend). When Pete finally dumps her for good after she’s been playing him off Ned Leeds for months, it made a certain amount of sense. With issue 34, she bailed and wasn’t much missed. Betty was a neurotic weakling, but she was admittedly very human and believable.

Betty and Liz were pushed off the stage by Gwen Stacy come ish 31. An icy beauty with a brain, who was fascinated by Pete’s academic record and challenged by his perceived standoffish-ness. Despite her striking appearance, Gwen in her Ditko incarnation was, well, complicated. She seemed feisty and prone to manipulative and devious means to get Peter’s attention, and prone to fits of temper when he disappointed her. But she didn’t lack confidence, that’s for sure.

In case you think we missed her, Mary Jane Watson began to appear with issue 25, after hanging around as a joke, mentioned, but never seen. She was the niece of a friend of Aunt May’s friend Anna May Watson, and Aunts was determined to fix her and Peter up. Pete, meanwhile, thwarted every attempt, convinced she must be ugly. Pete never did lay eyes on her during Ditko’s run, nor did we. But Liz and Betty did…

The Super-Hero As A Work In Progress

All of this leads me to the most interesting and unexpected part of this whole tale. Because over the course of these 37+ issues, Peter becomes less and less of an angst-ridden teen, and less-and-less and more less-and-less of a dork. The hapless guy who can’t get a girl to look at him twice forwardly (and smoothly) flirts back with his first crush (and gets her!), is pursued by the Prettiest Girl in School (High School Edition)and later by the Prettiest Girl in School (College Edition). The bully magnet gives notice that he can only be pushed so far – and proves it. Look – a guy who fights for his life against high-tech-weaponed and super-powered villains (including Doctor Doom) on a regular basis just isn’t going to be intimidated by schoolgirls or loudmouthed jocks. Ditko and Stan both got it, and worked it into the stories, as Peter’s growing self-confidence and inner strength began to show whether he intended them to or not. This was no accident – Betty and Gwen both notice it. This was something that had never happened in a super-hero series before.

Ditko’s Spider-Man was the best title in Marvel’s early galaxy. Much of that is due to Ditko’s bizarre imagination, iconoclastic themes, and humor. But much of that also is due to the fact that, reading through his run, you realize that you aren’t just reading about a young superhero – you’re also reading about a boy becoming a young man.

Obviously, for a blog with such a Marvel slant (so far), I have to say a few words about Stan Lee.

Obviously, for a blog with such a Marvel slant (so far), I have to say a few words about Stan Lee.